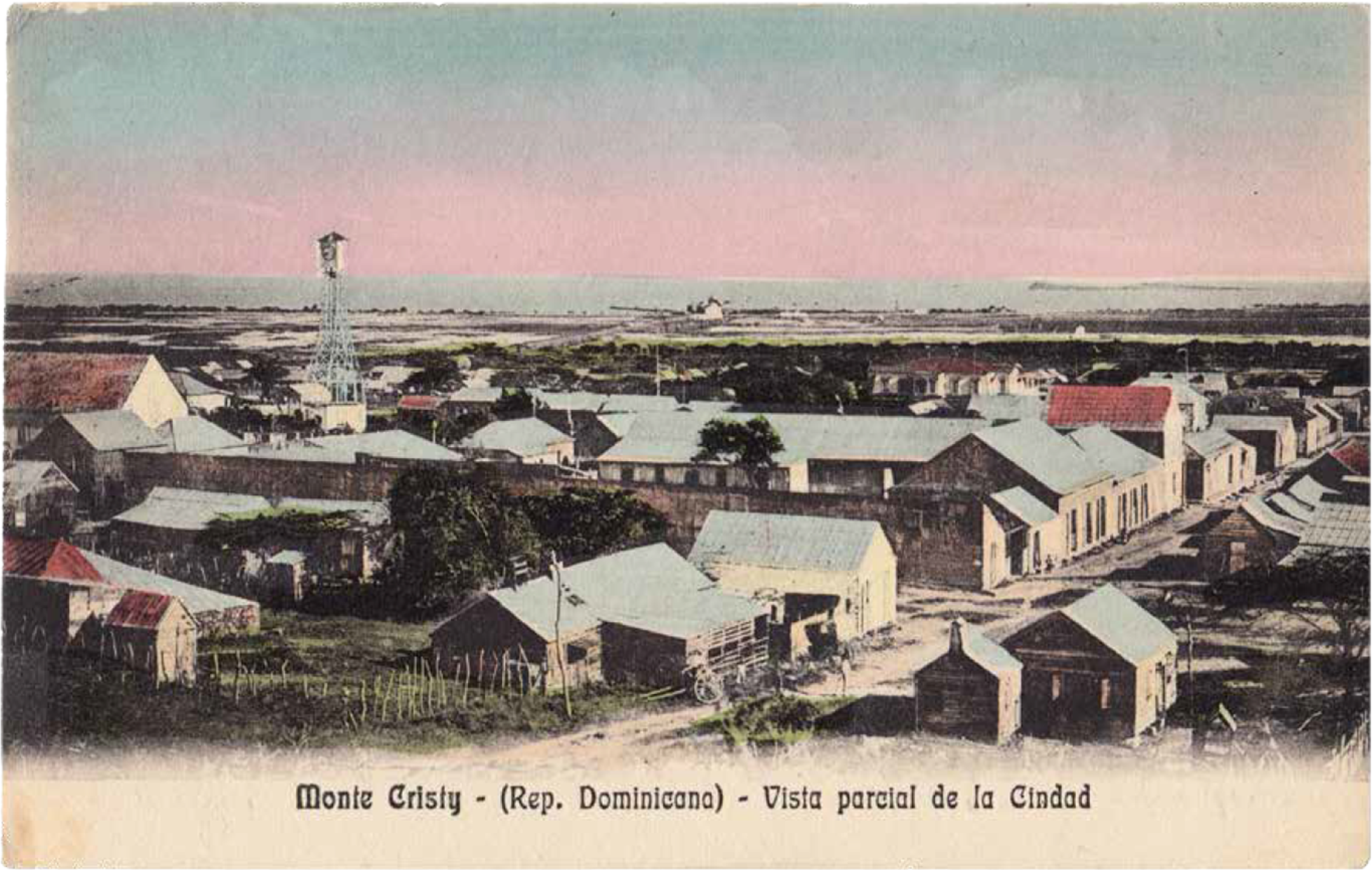

On top of that, another noteworthy event took place that same year: the Dominican Post Office produced and sent its peers around the globe a celebratory New Year’s card. Thus 1889 marked the gathering of a perfect storm, blending together a string of eye-catching situations: the desire to present the country internationally, the development of complex postal logistics and, beyond that, the awakening of our local printing industry. This explains why Miguel D. Mena used 1889 as the starting point of the story of an object that speaks of our national history in just two dimensions: the postcard.

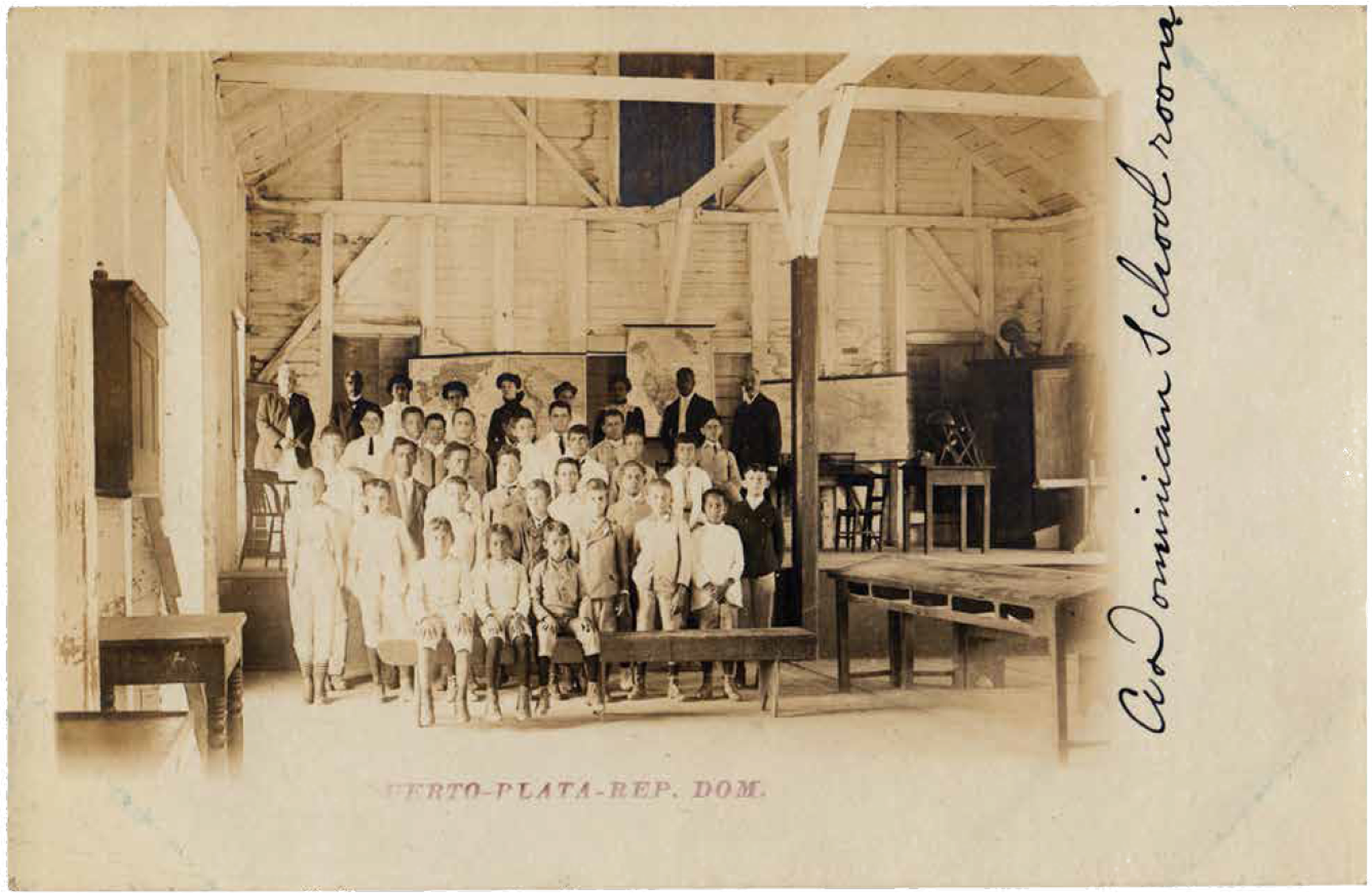

In Postcard Memories, the Dominican writer and essayist explains the context behind a spectacular print archive. Therein contained are the many ways in which our towns became cities, our everyday customs became our national identity and our aspirations became our reality.

From the Doctor’s Office to the… Tourist Office?

The Dominican Republic Comes Out

Imagining a Capital City

You Can Count on Us Dominicans

Our New Icons

Some Everyday Charms

Keeping Ourselves Occupied during the Occupation

Peace and Postcards

The Rise of a Modern Nation

Bring on the Tourists

Looking Back, Looking Forward

Textos y selección de imágenes

Fotografías

Dirección de Arte y Diseño

Traducción

Corrección ortotipográfica